Can We Really Increase our Home Values by Raising our Taxes?

A recent claim to Fairfield’s elected officials in support of the proposed BOE budget was as follows:

“It’s fact. Numerous research studies show that each additional dollar of local property taxes spent on education results in an increase in the grand list of approximately $34.27. That means property values go up when local education spending increases.”

DOES THIS SEEM TOO GOOD TO BE TRUE: “HOME VALUES GO UP WHEN TAXES ARE RAISED”? We thought so, and so we looked carefully at these “research studies.” Read on to see what we learned.

In support of this claim, a reference was provided to a single paper written[1] in 2006 by an associate professor at the University of Delaware while he was a member of his local Board of Education.

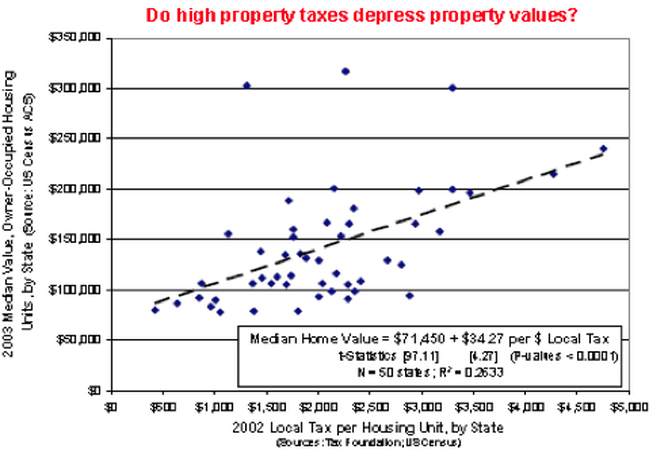

The absurdity of the author’s conclusion – that $1 in additional property taxes (which he then conflates with school taxes) produces $34.27 in higher property values (not “Grand List”) – should be readily apparent to anyone who bothers to read the paper. All the author has done is prove the obvious, which is: If you live in a more expensive house, you will pay more property taxes. He then twists this self-evident truth into the assertion that his graph proves that high property taxes do not depress property values,[2] contorts this assertion into the claim that “Higher school taxes clearly do not depress property values,” and then convolutes that claim into the conclusion that the more you pay in property taxes, the more your home will be worth.[3] This is exactly the same as saying that the more you pay in income taxes, the more income you will earn. Here is his graph:

[1] Written, but never published, let alone published in a peer-reviewed journal.

[2] His exact words are: “Figure 6 shows that states with high effective property tax rates [note that he is now equating “tax per housing unit” with “tax rate”] generally have higher median housing values.”

[3] His exact words are: “a simple regression analysis suggests that, ceteris paribus, each additional dollar of local property tax increases property values by an estimated average of $34.27.”

Moreover, even if the author’s conclusion were true – that our property values would rise $34.27 for every additional $1.00 we pay in property taxes – this would argue not for an increase in Fairfield’s spending, but for a reduction, since we currently have $60 in property value for every dollar we spend on public services [$1 / 0.02393 = $41.79 / 70% = $59.70]. Thus, we should spend more on public services only if we can generate at least $60 in value for every additional dollar unless we are willing to increase our tax rate relative to the towns with which we must compete to attract and retain tax-paying residents.

For the record, Fairfield Taxpayer has always agreed with proponents of education spending that good schools support property values in our Town. However, we have also noted that, as with most things in life (e.g., sun, chocolate, apple pie and ice cream), we can also have too much of a good thing. Thus, at some point, high spending on education, or any other public service, also hurts property values by raising taxes to levels that are not affordable or competitive. After 17 years when spending and taxes rose at 2.5x-3.0x the rate of inflation, our tax rates are now too high relative to surrounding towns, and if we don’t address this problem in the short term, we will eventually destroy our ability to sustain all that we love about Fairfield, including our fine schools, in the long run. We can’t be desirable if we are not affordable, and being affordable won’t matter if we are not desirable. We have to get the balance right.

We will also take this opportunity to repeat what we said in response to an earlier claim that “sixty years of economic research demonstrate how school system quality is correlated with higher property values,” which cited yet another study that stated that “an implicit demand for schools is reflected in the market value of every residential property.” Once again, we agree that good schools support property values. However, the problem with this argument is that during the 60 years of postwar prosperity that we all enjoyed, there is a correlation between education quality and literally everything else that happened, both good and bad, but that does not mean there is a causal relationship between educational quality and all those other things. With specific reference to the relationship between “education quality” and “property values,” it is far more likely that both benefit from favorable demographics and culture, and that both suffer from unfavorable demographics and culture, rather than that one of them causes the other. Though we may never be able to determine exactly which demographic-cultural “recipe” optimizes education quality and property values, one thing that studies consistently show is that additional spending on education beyond some reasonable threshold does not produce any measurable improvement in student performance. Some data even suggest the opposite, that higher spending beyond that threshold results in poorer outcomes.

Some Technical Rebuttal Points

With acknowledgement to one of Fairfield Taxpayer’s more quantitatively skilled participants, we offer the following additional criticisms of the paper under the suggested heading, “There is no free lunch.”

1. “Correlation” does not mean or imply “causation,” and in fact, the R2 (formally defined as the correlation of determination) in this “analysis” is only 26.33%. This means that only 26.33% of the variation in median home prices in the U.S. from one state to another, in a single year, more than ten years ago, is explained by differences in the amount of property taxes. Thus, even if there were a basis for presuming some causal relationship, the author fails to note that 73.67% of the differences in his dependent variable (median home values) are explained by something else.

2. The slope of the regression line in this “analysis” (which is the source of the $34.27 number) is subject to many obvious qualifications, including: (a) the degree to which a given state depends on local property taxes rather than other sources of revenues, such as federal transfer payments, income taxes and sales taxes, to pay for public services; and (b) the degree to which wealthy states rely on property taxes relative to poorer states. For example, if all states had the same mix of housing (i.e., if their median home values were equal) and the same reliance on property taxes, the regression line might well be flat. The author does not explain, for example, why, if higher property taxes raise home values, a line fitted to the three outliers in the above graph would be flat, reflecting the fact that California, Hawaii and Massachusetts all have equally high median home values despite very different levels of property taxes per housing unit.

3. The author’s conclusion fails to recognize the law of diminishing returns: While the first dollar invested may yield a high return on investment, as the rate of spending increases, the marginal benefit or return on investment decreases. Thus, the question is not, as it was 375 years ago in 1639, whether Fairfield should spend the first dollar on public services, but whether a reasonable rate of return can be obtained on additional public spending from the current level, in the current general economic environment, and given our current competitive position relative to surrounding towns and states.

4. The “analysis” is based on highly aggregated state-level data, and it is difficult to see how such a large data set with such a modest R2 that is subject to all of the aforementioned underlying assumptions is relevant to a particular town or school district in Southwestern CT, since our town and state are faced with so many unique socio-economic, demographic and competitive conditions.

5. The “analysis” is based on data for one particular point in time. It is a “snapshot” of 2002/2003. There is no longitudinal data that might disclose a trend in the relationship between property taxes and median home values. For example, it is quite possible that the trend in median home values is down in all states that have been increasing property taxes and up in all states that have been reducing them.

6. The author’s conclusion (“Higher school taxes clearly do not depress property values”) is similar to those of economists who believe that government spending in general is highly beneficial because of its so-called, “multiplier effect” (i.e., the more money government spends, the better, because it stimulates general economic growth and promotes the general welfare). Other economists argue that the government spends money much less efficiently than the private sector, and that if government spending worked so well in the real world, we and Greece could simply spend and tax ourselves into perpetual prosperity.

http://www.udel.edu/johnmack/research/school_funding.pdf

A recent claim to Fairfield’s elected officials in support of the proposed BOE budget was as follows:

“It’s fact. Numerous research studies show that each additional dollar of local property taxes spent on education results in an increase in the grand list of approximately $34.27. That means property values go up when local education spending increases.”

DOES THIS SEEM TOO GOOD TO BE TRUE: “HOME VALUES GO UP WHEN TAXES ARE RAISED”? We thought so, and so we looked carefully at these “research studies.” Read on to see what we learned.

In support of this claim, a reference was provided to a single paper written[1] in 2006 by an associate professor at the University of Delaware while he was a member of his local Board of Education.

The absurdity of the author’s conclusion – that $1 in additional property taxes (which he then conflates with school taxes) produces $34.27 in higher property values (not “Grand List”) – should be readily apparent to anyone who bothers to read the paper. All the author has done is prove the obvious, which is: If you live in a more expensive house, you will pay more property taxes. He then twists this self-evident truth into the assertion that his graph proves that high property taxes do not depress property values,[2] contorts this assertion into the claim that “Higher school taxes clearly do not depress property values,” and then convolutes that claim into the conclusion that the more you pay in property taxes, the more your home will be worth.[3] This is exactly the same as saying that the more you pay in income taxes, the more income you will earn. Here is his graph:

[1] Written, but never published, let alone published in a peer-reviewed journal.

[2] His exact words are: “Figure 6 shows that states with high effective property tax rates [note that he is now equating “tax per housing unit” with “tax rate”] generally have higher median housing values.”

[3] His exact words are: “a simple regression analysis suggests that, ceteris paribus, each additional dollar of local property tax increases property values by an estimated average of $34.27.”

Moreover, even if the author’s conclusion were true – that our property values would rise $34.27 for every additional $1.00 we pay in property taxes – this would argue not for an increase in Fairfield’s spending, but for a reduction, since we currently have $60 in property value for every dollar we spend on public services [$1 / 0.02393 = $41.79 / 70% = $59.70]. Thus, we should spend more on public services only if we can generate at least $60 in value for every additional dollar unless we are willing to increase our tax rate relative to the towns with which we must compete to attract and retain tax-paying residents.

For the record, Fairfield Taxpayer has always agreed with proponents of education spending that good schools support property values in our Town. However, we have also noted that, as with most things in life (e.g., sun, chocolate, apple pie and ice cream), we can also have too much of a good thing. Thus, at some point, high spending on education, or any other public service, also hurts property values by raising taxes to levels that are not affordable or competitive. After 17 years when spending and taxes rose at 2.5x-3.0x the rate of inflation, our tax rates are now too high relative to surrounding towns, and if we don’t address this problem in the short term, we will eventually destroy our ability to sustain all that we love about Fairfield, including our fine schools, in the long run. We can’t be desirable if we are not affordable, and being affordable won’t matter if we are not desirable. We have to get the balance right.

We will also take this opportunity to repeat what we said in response to an earlier claim that “sixty years of economic research demonstrate how school system quality is correlated with higher property values,” which cited yet another study that stated that “an implicit demand for schools is reflected in the market value of every residential property.” Once again, we agree that good schools support property values. However, the problem with this argument is that during the 60 years of postwar prosperity that we all enjoyed, there is a correlation between education quality and literally everything else that happened, both good and bad, but that does not mean there is a causal relationship between educational quality and all those other things. With specific reference to the relationship between “education quality” and “property values,” it is far more likely that both benefit from favorable demographics and culture, and that both suffer from unfavorable demographics and culture, rather than that one of them causes the other. Though we may never be able to determine exactly which demographic-cultural “recipe” optimizes education quality and property values, one thing that studies consistently show is that additional spending on education beyond some reasonable threshold does not produce any measurable improvement in student performance. Some data even suggest the opposite, that higher spending beyond that threshold results in poorer outcomes.

Some Technical Rebuttal Points

With acknowledgement to one of Fairfield Taxpayer’s more quantitatively skilled participants, we offer the following additional criticisms of the paper under the suggested heading, “There is no free lunch.”

1. “Correlation” does not mean or imply “causation,” and in fact, the R2 (formally defined as the correlation of determination) in this “analysis” is only 26.33%. This means that only 26.33% of the variation in median home prices in the U.S. from one state to another, in a single year, more than ten years ago, is explained by differences in the amount of property taxes. Thus, even if there were a basis for presuming some causal relationship, the author fails to note that 73.67% of the differences in his dependent variable (median home values) are explained by something else.

2. The slope of the regression line in this “analysis” (which is the source of the $34.27 number) is subject to many obvious qualifications, including: (a) the degree to which a given state depends on local property taxes rather than other sources of revenues, such as federal transfer payments, income taxes and sales taxes, to pay for public services; and (b) the degree to which wealthy states rely on property taxes relative to poorer states. For example, if all states had the same mix of housing (i.e., if their median home values were equal) and the same reliance on property taxes, the regression line might well be flat. The author does not explain, for example, why, if higher property taxes raise home values, a line fitted to the three outliers in the above graph would be flat, reflecting the fact that California, Hawaii and Massachusetts all have equally high median home values despite very different levels of property taxes per housing unit.

3. The author’s conclusion fails to recognize the law of diminishing returns: While the first dollar invested may yield a high return on investment, as the rate of spending increases, the marginal benefit or return on investment decreases. Thus, the question is not, as it was 375 years ago in 1639, whether Fairfield should spend the first dollar on public services, but whether a reasonable rate of return can be obtained on additional public spending from the current level, in the current general economic environment, and given our current competitive position relative to surrounding towns and states.

4. The “analysis” is based on highly aggregated state-level data, and it is difficult to see how such a large data set with such a modest R2 that is subject to all of the aforementioned underlying assumptions is relevant to a particular town or school district in Southwestern CT, since our town and state are faced with so many unique socio-economic, demographic and competitive conditions.

5. The “analysis” is based on data for one particular point in time. It is a “snapshot” of 2002/2003. There is no longitudinal data that might disclose a trend in the relationship between property taxes and median home values. For example, it is quite possible that the trend in median home values is down in all states that have been increasing property taxes and up in all states that have been reducing them.

6. The author’s conclusion (“Higher school taxes clearly do not depress property values”) is similar to those of economists who believe that government spending in general is highly beneficial because of its so-called, “multiplier effect” (i.e., the more money government spends, the better, because it stimulates general economic growth and promotes the general welfare). Other economists argue that the government spends money much less efficiently than the private sector, and that if government spending worked so well in the real world, we and Greece could simply spend and tax ourselves into perpetual prosperity.

http://www.udel.edu/johnmack/research/school_funding.pdf